by J Michael Waller, Reader’s Digest, June 1996

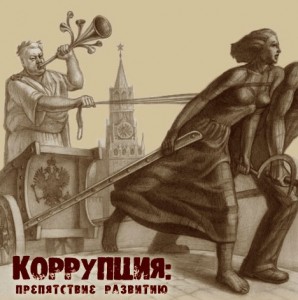

Nearly five years after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the unthinkable is occurring: The Community Party once again dominates the Russian parliament. Free-market reformers in Boris Yeltsin’s government have been purged, and Yeltsin has distances himself from the West. Yevgeny Primakov, a former chief of foreign intelligence who backed countries that supported terrorism, is foreign minister. And a new nuclear-weapons program is under way.

All this has happened despite a commitment of more than $20 billion in U.S. aid, financing, trade subsidies and buyouts to back Moscow’s reform efforts. In fact, U.S. aid has discouraged reform by abetting organized crime and official corruption.

Money that was supposed to jump-start the private sector has instead enriched the old Communist ruling class. And money intended for dismantling the Soviet nuclear stockpile is being frittered away while Russia rebuilds its arsenals.

The result is a profound foreign-policy failure that threatens U.S. security. “Not only do we fail to influence the course of Russian reforms, we actually create an anti-American backlash built on disappointed expectations,” says Sen. Bill Bradley (D., N.J.).

Gangster Bureaucrats

Until 1991 the Soviet government and its ruling Communist Party owned virtually everything — from local shops to vast farms and factories. With communism’s collapse, reformers hoped that privatization would let Russian citizens own a stake in the new system.

The U.S. government has committed $355 million for a variety of programs to encourage free enterprise. But huge chunks of the money appear to have been misused by what Toronto Star international-affairs columnist Stephen Handelman calls Moscow’s “gangster bureaucrats.”

American University professor Louise Shelley, an authority on Russian crime and corruption, cites a large construction project in St. Petersburg that was bought by organized crime. Today signs in front of the project boast that it is being funded by U.S.-backed multilateral development banks.

It all began with good intentions. In 1992 the U.S. Agency for International Development (AID) underwrote a $63 million program to give every Russian citizen a voucher worth about $30, to invest in privatized properties. But the vouchers didn’t hold their value, and Communist managers bought up millions of them to retain control of the enterprises.

In Russia’s Orel region, 2000 workers at an electronic instrument plant were forced to go on leave while managers illegally purchased the controlling share of the company. In the Vologda region, two-thirds of the shares of a cement plant were registered in the names of the plant director and his mother-in-law.

To make matters worse, millions of extra vouchers were illegally produced, Shelley says. Then organized crime rigged or blocked access to auctions where state property was being sold, and used the forged vouchers to buy up real estate. The Russian press reported that buyers for as much as 70 percent of the auctioned real estate were agreed upon beforehand.

As the average citizen lost his stake in the new Russia, former Communists, who make up less than ten percent of the population, prospered. Surveys of Russia’s new rich found that nearly two-thirds of the country’s millionaires had been members of the Soviet Communist Party. The KGB, too, has profited by operating in such businesses as banks, trading houses and telecommunications. Many Russian joint ventures with Western companies include KGB officers.

Farm Fiasco

Early on, AID spent tens of millions of dollars on technical training and exchange programs, in part to support independent farmers. The results were encouraging. When the Soviet Union dissolved, there were only 4500 private farms in Russia. Two years later there were more that 183,000, some with higher crop yields than collectives and state farms.

Then Washington began to ship in massive quantities of subsidized grain, deeply depressing prices in Russia and hurting the small, private grain producers. To help those struggling farmers, U.S.-donated grain would be sold for rubles, with the proceeds placed in trust funds and loaned to the private farmers to develop infrastructure.

In the Saratov region, such loans were promised to help private farmers construct permanent, cost-effective grain storage facilities, free from control of the old state monopolies. Those silos were never built. Some officials suspect that the old Soviet networks not only ran the distribution systems for American grain, but also owned the banks through which the loans were administered — effectively blocking the program. Brian Foster, an Iowa farmer who has directed successful AID-funded Russian projects, told Reader’s Digest, “The U.S. taxpayer got snookered.”

To add insult to injury, much of the American grain that went through Russian state monopolies wound up being wasted or stolen. Colorado businessman David Wolstenholme says, “I’ve walked through dozens of Russian warehouses filled with American food products salted away for later sale abroad or on the black market.”

Stuffed With Cash

Soon after the Soviet Union collapsed, the new Russian government asked the West for billions of dollars in grants and loans. Its petition went before the International Monetary Fund (IMF), a global financial institution in which the United States is the largest contributor. At first, with Washington’s urging, the IMF quickly loaned Russia $1 billion in 1992 and another $1.5 billion in 1993. Reformist finance minister Boris G. Fyodorov rejected a third loan, saying Moscow continued to subsidize huge, inefficient state industries. Frustrated by this, Fyodorov registered, and the IMF balked at further loans. Yeltsin called on President Clinton to pressure the IMF to send more money.

The Administration responded. In December 1993, according to the New York Times, Vice President Al Gore blasted the IMF for being too hard on Moscow, accusing it of making austerity demands that would provoke a nationalist backlash. The IMF relented and in April 1994 released another $1.5 billion. More was to come. In early 1995 the INF extended a roughly $6-billion loan. And last March it approved about $10 billion to be delivered over the next three years.

Total to date: more than $20 billion. “This money corrupts the system,” says Fyodorov. Even worse, he says, many top Russian leaders have no intention of repaying the loans.

Last year the funds were being transferred to Russia in monthly payments equaling about $17 million a day. At the same time, according to Russian news reports, an average of $50 million a day is being pumped out of the country to private bank accounts in Switzerland, Cyprus and elsewhere.

In a letter, Moscow-based Italian journalist Giulietto Chiesa told the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee that money is stuffed aboard airplanes, “many of which get over the border with the help of highly placed persons in the government.”

Other AID programs have subsidized massive Soviet-era businesses and well-connected political leaders. AID has allocated $3.2 million for U.S.-made equipment for Gazprom, the vast natural-gas monopoly founded by Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin, in a deal engineered by a commission overseen by Vice President Gore. Meanwhile, the supposedly struggling Gazprom bought two executive jets valued at about $50 million.

David H. Swartz, the first U.S. ambassador to Belarus, a former Soviet republic, witnessed the misuse of funds firsthand. When Washington sent millions of dollars in agricultural commodity aid to the old-line Communists who control grain distribution, a top Belarussian reformer asked Swartz, “If the United States wants to foster reform here, who do you keep on supporting the Communists?”

“Good question,” replied the ambassador. He resigned in protest over American policy in 1994.

War Games

American aid funneled through the Cooperative Threat Reduction program was to help Russia destroy its nuclear, nerve-gas and germ-warfare weapons. Instead, U.S. aid has helped dismantle mostly obsolete military equipment Moscow wanted to scrap anyway.

Another botched program would pay up to $12 billion over the next two decades for Russian nuclear fuel made from dismantled warheads. However, because the U.S. government failed to link inspection of warheads to aid, officials have yet to verify whether the Russians are dismantling warheads or simply selling us surplus uranium. Far from helping reduce Moscow’s nuclear-warhead stockpile, the Clinton Administration has actually expanded it by paying for warheads from Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine that are transferred to Russia, away from the eyes of U.S. military monitors.

While Russia insists it is too broke to dismantle its weapons, it forges ahead with clandestine weapons development — helped by the United States. For example, Moscow’s International Science and Technology Center (ISTC) began operating in 1994 with a commitment of $35 million from the United States and other Western countries. The ISTC is supposed to give civilian work to “former weapons scientists” to prevent them from working for countries such as Iran and Iraq.

Investigators from Congress’s General Accounting Office (GAO) found, however, that many scientists put in only a few hours a week at the center, raising the prospect that they spent the rest of their time doing “their institutes’ work on weapons of mass destruction.” That work included nerve-gas research and nuclear-weapons development. The GAO found that one of the U.S.-funded projects at ISTC was a high-tech camera that can be used to record the process of explosions in nuclear-weapons tests.

In fact, Russia is still building nuclear weapons. Last year Viktor Mikhailov, chief of Minatom, the Russian Ministry of Atomic Energy, boasted about production of what a Moscow newspaper termed “new, cheaper and more effective nuclear munitions.” Weeks later, Vice President Gore signed a protocol in Moscow to provide a $100-million advance on the $12-billion uranium purchase.

Last September the Russian military launched an ultramodern intercontinental ballistic missile prototype code-named TOPOL-M. Other test launches have followed.

Even though Moscow forges ahead with secret development of deadly nerve gases, the Clinton Administration is giving the green light to fund a chemical-analysis laboratory at the very institute where the research is taking place. The U.S.-funded lab is intended to help Russian chemical-weapons scientists develop means to destroy nerve-gas stockpiles.

But Vil Mirzayanov, a veteran scientist of 26 years at the State Union Scientific Research Institute for Chemistry and Technology, who blew the whistle on large-scale clandestine nerve-gas development in 1992, has warned that any such U.S. aid will only keep the R&D teams together to continue their lethal work. And Russian officials still deny U.S. inspectors access to certain nerve-gas facilities.

Some Russian reformers say that U.S. aid should be supplied only under strict conditions. Unfortunately, even the most piecemeal restrictions have proved impossible to implement.

In fact, there’s no practicable way to enforce conditions. The United States can do more for much less money by cutting off economic aid to the Russian government and helping private citizens directly.

Medical surplus delivered to supply-starved hospitals in Vladivostok and elsewhere allow average citizens to benefit from American generosity. Training programs, sponsored by the Center for International Private Enterprise, have helped educate fledgling businessmen. Low-budget, high-impact citizen exchanges sponsored by the U.S. Information Agency have helped elected officials in the fight against crime.

But the 1996 budgets for some of these inexpensive, productive projects have been slashed, while the multibillion-dollar cash bailouts of the corrupt regime have ballooned.

Nothing could be more foolhardy than to ignore the many Russians who are trying to make democracy prevail against the criminals, Communists and ultranationalists. “In no event should the West turn away from Russia and leave it to its fate,” says Sergei Kovalev, a former political prisoner and current reformer in the parliament. “That would leave Americans and other nations with a dangerous, aggressive, unpredictable neighbor.”

Congress and the Clinton Administration must stop trying to salvage the discredited Russian government. “Current policy is destructive to our own interests,” says former Under Secretary of State William Schneider, Jr. “We are propping up a reactionary and unpopular regime and saving the old guard.”

Copyright © 1996, The Reader’s Digest Association. Reprinted with permission.

1 thought on “To Russia, with cash”

Comments are closed.