by J Michael Waller / Serviam / January 2, 2009.

First Sergeant Roland Williston lay on a gurney in the 100-degree Virginia heat, with gangrene consuming the amputated stumps of his shattered left hand and leg. The 26-year-old barber from Holyoke, Mass., had been among the first volunteers to answer President Abraham Lincoln’s call to save the Union. Now, in the sweltering humidity of a sick bay swarming with flies, he knew he would never see home again.

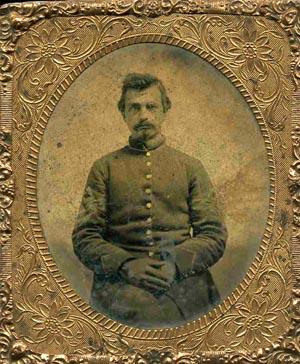

First Sergeant Roland Stebbins Williston was one of the first mortally wounded soldiers to receive assistance from Clara Barton and what would become the American Red Cross.

Williston’s unit, the Second Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, was the last federal force left standing on that terrible day of August 9, 1862, when ill-prepared Union troops engaged a superior Confederate force at Cedar Mountain near Culpeper, Va. The only Civil War engagement in which Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson would draw his sword, the battle was in part the product of the Union army’s own poor planning.

The battle also marked the start of something new—something that would bring relief to the sick and wounded and hope to the hopeless millions of times over. It marked the first time that Clara Barton, who would found the American Red Cross, ministered to soldiers in the field, becoming a harbinger of today’s global stability industry.

Barton was a true pioneer in getting more efficient, private-sector support to the military, as she was in advancing the cause of women’s rights. A 40-year-old U.S. Patent Office clerk in Washington, D.C., when the war began in 1861, she was horrified at the plight of the wounded young men flooding the nation’s capital from the battlefields. The Army Medical Department, she noted, was terribly unprepared to treat casualties.

Inspired by her father, who urged her to devote her life to patriotic and charitable causes, Clara Barton lobbied the army for months to allow her to go directly to the front with her own medical supplies. The army wouldn’t hear of it. Finally, in April 1862, after the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas), Gen. William Hammond issued her a pass to travel with wounded soldiers in army ambulances.

But she was still not allowed in the combat areas. In those times, few single women of good repute traveled with the rough and lonely soldiers. Military camps were no place for ladies. Barton and her volunteers, though, were undaunted. By summer, thanks to the intervention of Senator Henry Wilson of her home state of Massachusetts, the army relented.

Barton, her volunteers, and their small mule train of supplies reached Culpeper, Va., four days after the Battle of Cedar Mountain. With army surgeons and medics grotesquely overworked and lacking many of the most basic supplies, the Barton group spent two days and two nights tending to wounded and dying Union soldiers, stopping later to tend to Confederates as well. When they could do nothing to heal the wounded or lessen their pain in the stinking heat, they comforted them as best they could, washing them, listening and talking with them, and singing or praying as they closed their eyes to fall asleep or die.

The military was already experiencing technological advances, from using the telegraph and railroads for rapid communication and logistics to employing new classes of rifles, artillery, and other industrialized products on the battlefield. Barton was another aspect of that change: Her nongovernmental organization outside the military chain of command would now play an important role in warfare and its aftereffects. She would revolutionize how the U.S. military took care of its wounded, its veterans, and its dead.

Barton and her volunteers were present at Second Manassas, the carnage at Antietam, and Fredericksburg. At Antietam, a bullet ripped through her sleeve, killing the man she was assisting. By 1863, the Army Medical Department was better equipped to meet the needs of the military, and Barton’s efforts were tiny in comparison. She remained on the fronts. In 1865, Barton started a nationwide campaign to identify missing soldiers, helping with the identification of 13,000 Union unknowns buried at the Andersonville, Ga., prison camp.

She went to Europe on doctors’ orders, only to be convalescing at the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. Back in action, Barton assisted with the French relief effort, where she discovered the volunteers of the Red Cross, a charitable group that had been founded in Switzerland while she was working in the battlefields of the American South.

Returning to the United States, she started organizing the American chapter of the Red Cross in 1873. Congress recognized the American Red Cross in 1881 as a private aid provider in time of disaster. Industrialist John D. Rockefeller provided the resources to buy a parcel of land one block from the White House and build a magnificent marble headquarters building.

In 1905, Congress chartered the American Red Cross to “carry on a system of national and international relief in time of peace and apply the same in mitigating the sufferings caused by pestilence, famine, fire, floods, and other great national calamities, and to devise and carry out measures for preventing the same.” In World War I, the surgeon general enlisted the American Red Cross to set up 58 base hospitals in Europe. The American Red Cross recruited more than 104,000 registered nurses to serve in military hospitals. The group served similarly in the Korean War, Vietnam, the Persian Gulf War, Somalia, the Balkans, and the Middle East, and continues to assist today in Afghanistan and Iraq.

At home, the American Red Cross responds to more than 70,000 disasters a year, from house fires to hazardous waste spills, from tornadoes to earthquakes. It provides 3,000 American hospitals with blood and blood products and assists 1.4 million active duty military families and 1.2 million members of the National Guard and Reserves. An innovation that began as an unwanted intrusion on the military is now a national institution.