J Michael Waller / Insight magazine / January 24, 2000 – Is your individual retirement account bankrolling Communist China’s nuclear-weapons program? Is that promising oil stock in your portfolio financing a war of extermination against Christians halfway around the world? Could your pension fund be weakened because it holds shares in companies about to be slapped with sanctions for investing in terrorist regimes? Chances are you don’t know, even if you read the fine print in the prospectus.

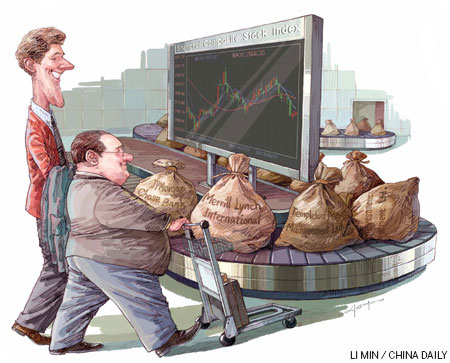

Nuclear proliferators, terrorist states, foreign scam operators and Third World mass murderers literally have been banking on the failure of the United States to demand adequate transparency and disclosure of the equities and bonds they introduce in U.S. capital markets. As a result, unwitting American investors potentially have been pumping their cash into everything from Russian organized crime to a vicious ethnic-cleansing campaign in Africa to peddlers of weapons of mass destruction in Communist China. The big New York financial houses don’t seem to care, say critics, as long as the money rolls in – and the Asia growth funds that hold Chinese state firms are among the higher performers in the market.

No bank or brokerage house, no business-news organization and no government agency comprehensively follows People’s Republic of China, or PRC, penetration of U.S. capital markets. Indeed, the first public exposure of this problem appeared in Insight in an article by Timothy W. Maier (see “PLA Espionage Means Business,” March 24, 1997, and “U.S. Is Financing China’s War Plan,” May 12, 1997).

A special House panel led by Rep. Christopher Cox, a California Republican, since has investigated Beijing’s technological theft and found that the Securities and Exchange Commission, or SEC, “collects little information helpful in monitoring PRC commercial activities in the United States. This lack of information is due only in part to the fact that many PRC front companies are privately held and ultimately – if indirectly – wholly owned by the PRC and the Chinese Communist Party itself. Increasingly, the PRC is using U.S. capital markets both as a source of central-government funding for military and commercial development and as a means of cloaking U.S. technology-acquisition efforts by its front companies with a patina of regularity and respectability.”

A bipartisan panel headed by former CIA director John Deutch has probed the threat of proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and also voiced concern that “known proliferators may be raising funds in the U.S. capital markets.” The Deutch commission warned, “Because there is currently no national-security-based review of entities seeking to gain access to our capital markets, investors are unlikely to know that they may be assisting in the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction by providing funds to known proliferators. Aside from the moral implications, there are potential financial consequences of proliferation activity – such as the possible imposition of trade and financial sanctions – which could negatively impact investors.”

Because of growing public awareness, however, this situation may be changing. Lack of transparency and disclosure was at the heart of the emerging-markets financial crisis, and Communist China is among the most opaque even though state-owned PRC entities have raised about $14 billion in dollar-denominated bonds since 1980. Now, a bipartisan initiative in Congress as well as nongovernmental grass-roots movements are turning up the heat – just in time for an expected initial public offering on the New York Stock Exchange of a state-run oil company with ties to terrorist regimes.

Some California legislators were outraged last year when they discovered that CalPERS, the powerful California Public Employees’ Retirement System, never considered national-security concerns in its investment decisions. State Sen. Raymond Haynes, citing a July 1999 report by Investors Business Daily’s John Berlau, is concerned that California pension-fund holders unwittingly are funding the Chinese military. With more than $150 billion in holdings, CalPERS is the second-largest pension fund in the world. The newspaper report targeted four CalPERS holdings: CITIC Pacific Ltd., CITIC Ka Wah Bank, COSCO Pacific Ltd. and China Resources. CalPERS Chairman Charles Valdes blasted the article as “modern-day `McCarthyism’ at its worst.”CITIC is the acronym for the China International Trade and Investment Corp., a huge mainland conglomerate that is integrated into the Beijing government through the People’s Liberation Army, or PLA. COSCO, the China Ocean Shipping Co., is the PLA merchant marine.

And China Resources, according to Sen. Fred Thompson, the Tennessee Republican who led a probe of secret Chinese funding of the Clinton-Gore reelection effort, is “an agent of espionage – economic, military and political – for China.” CalPERS rejects all military and espionage concerns and goes even further by asserting that it doesn’t care whether it invests in Chinese enterprises which act in ways harmful to the United States.

A lengthy statement from the CalPERS public-relations office says CITIC Pacific is “a highly respected investment house in Hong Kong, led by a Stanford graduate.” CalPERS insists that CITIC Pacific isn’t affiliated with CITIC though the latter is a shareholder, but the Wall Street Journal describes CITIC as “the parent of CITIC Pacific” and says the latter is the Beijing conglomerate’s “Hong Kong-listed unit.”

COSCO, according to the pension fund, is completely benign as “the second-largest shipping company in the world, with a significant employee population in the San Diego area.” China Resources, claims CalPERS, isn’t what critics say it is; rather, it is “the principal world outlet for Chinese arts and crafts.”

CalPERS says Thompson’s espionage allegations about China Resources are unproved, “nor is information of this type relevant to purchasing decisions by the pension fund.”

“That explanation right there illustrates why we need full transparency and disclosure,” counters Assemblyman Steve Baldwin, vice chairman of the California Assembly’s Education Committee. Baldwin tells Insight, “If we can’t even depend on our own state pension fund to tell us the truth, we’ve got a real problem.”

CalPERS justified its holding of CITIC Pacific, China Resources and COSCO Pacific by saying that the Texas teachers pension fund also owns shares. But instead of attacking the Investors Business Daily report, Texas took the allegations seriously and acted. State Rep. Suzanna Gratia Hupp approached all her colleagues and the board members of teacher pension funds. The funds eventually decided to divest from the PLA merchant marine. The Texas Teachers’ Retirement System claims the divestment was part of the normal rotation of its portfolio.

From Capitol Hill, Reps. Spencer Bachus, an Alabama Republican, and Dennis Kucinich, an Ohio Democrat, sent letters to all 50 state treasurers and attorneys general last August and again in November, urging them to review state investment portfolios for stocks and bonds in foreign-government-related firms that may threaten U.S. national security.

Response has been mixed. Iowa state Treasurer Michael Fitzgerald, a Democrat, strongly defends the Iowa Public Employees Retirement System’s investments in CITIC, COSCO and China Resources, even though those investments (totaling less than $2.5 million) are relatively small. Contrarily, Drew Pearce, Republican president of the Alaska state Senate, says she supports a national-security audit of her state’s $30 billion retirement fund. In the Golden State, some California lawmakers want to challenge CalPERS. Baldwin tells Insight he intends to introduce a bill this spring mandating that the state-employees’ fund disinvest from Communist Chinese enterprises.

In the nation’s capital, meanwhile, momentum is building to clamp down on governments and their corporate affiliates that raise money in U.S. markets for terrorism, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, wars of extermination and building nuclear missiles aimed at U.S. cities. On the surface, this seems noncontroversial. But apart from the handful of investment bankers who make fortunes from such deals, and former U.S. officials peddling influence for Beijing, there still is a concern that empowering the SEC to monitor stock and bond offerings would harm the free flow of capital.

The Deutch commission urged the creation of a national director for combating proliferation who would consult with interagency as well as private-sector experts to “assess options for denying proliferators access to U.S. capital markets.

Options considered should include ways to enhance transparency, such as requiring more detailed reporting on the individuals or companies seeking access or disclosure of proliferation-related activity, as well as mechanisms to bar entry of such entities into U.S. capital markets.”

Bachus and Kucinich introduced a bill to create a new Office of National Security within the SEC which merely would report the names of firms affiliated with foreign governments and seeking to enter U.S. capital markets. That bill, the Market Security Act, is bogged down in committees, but separate transparency mechanisms might be developing on their own – free of any new law or regulation. (See sidebar below.)

The biggest initial public offering, or IPO, ever to hit Wall Street is snagged right now because of transparency concerns. The state-owned China National Petroleum Corp., or CNPC, with Goldman Sachs as its lead investment bank, has been planning an IPO that is expected to raise $5 billion to $10 billion. CNPC produces about two-thirds of mainland China’s crude oil, fueling a market expected to grow fivefold by 2009 and controlling oil fields in North Africa and the Middle East. But the CNPC’s entry on the New York Stock Exchange might not happen if a broad coalition of religious and human-rights leaders, lawmakers and national-security experts has its way.

CNPC’s great strength is its greatest weakness. Not only does it fuel a growing communist military machine at home, but it’s heavily invested in Iraq and the ugly slave state of Sudan – both on the State Department list of terrorist regimes. Rather than depend on market mechanisms to secure its ballooning need for fossil fuel, Beijing prefers to take physical control of the oil fields. CNPC has spent an estimated $1.5 billion to $2 billion on oil infrastructure in Sudan, its largest foreign commitment. It owns 40 percent of Sudan’s Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Co. projects, which will produce an estimated 150,000 barrels of oil a day. CNPC’s investment is augmented by a staggering $15 billion infrastructure commitment from the Chinese Communist government.

This investment has provoked a wave of revulsion and a backlash. According to State Department and U.N. reports, the Sudanese regime, led by ethnic Arabs who embrace an extreme mutation of Islamic fundamentalism, harbors international terrorists and is waging a war of extermination against the black and predominantly Christian population in the south. Some reports find the government complicit in the slave trade of black Christians, who are purchased and forced to work as servants, laborers or sex slaves.

A combination of war and government-induced famine has left more than 2 million mostly non-Muslim black Sudanese dead (see “China’s Abuses Ignored for Profit,” Dec. 20, 1999).”More people have died in Sudan than in Kosovo, Bosnia, Somalia and Rwanda combined,” according to Rep. Frank Wolf, a Virginia Republican who has visited the country three times during the last decade. “Most of the dead are civilians.”

In a letter to SEC Chairman Arthur Levitt, Wolf wrote, “The government of Sudan has announced publicly that it will use the oil revenue to increase the momentum and lethality of the war.” He added, “Allowing the CNPC to raise capital in the U.S. would exacerbate the already tragic situation in Sudan. It would also make it easier for Americans to invest, perhaps unknowingly, in a company that is propping up a regime engaged in slavery, genocide and terrorism.” Wolf urged the SEC to block CNPC’s public offering.

Some are going even further, urging disinvestment from companies that pour cash into the Sudan regime. In December, a coalition of 200 religious and human-rights leaders from mainline Catholic, Protestant, Evangelical and Jewish organizations called on President Clinton to “take a visible, personal stance on the genocide now taking place in Sudan.”

The group, led by Diane Knippers of the Institute on Religion and Democracy and Nina Shea of Freedom House, urged him to bar “the China National Petroleum Corp. and others who are investing with the genocidal regime in Khartoum from U.S. capital markets.”

Under the umbrella of the American Anti-Slavery Group, the divestment coalition transcends ideological and political boundaries, from Christian evangelicals to Rep. Donald Payne, a New Jersey Democrat and a leader of the Congressional Black Caucus.

The Washington Post has editorialized that Khartoum “declares that it will use its new oil wealth to stock up on military gear and win a victory on the battlefield. The government is bent on ethnic cleansing of territory surrounding other, as yet unexploited, oil fields. Once it has control of these, it will purchase yet more tanks and missiles.”

Bishop Macram Gassis of Sudan is quoted on the American Anti-Slavery Group Website as saying, “If the oil is pumped, we are finished. The Sudanese government will then be able to buy the weapons to wipe us out completely. Why are Western companies aiding in this pipeline project? No human life – no innocent Sudanese life – should be sacrificed to the pursuit of this oil money.”

Even more astoundingly, say backers, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright has joined the crusade, twice stating support for what she called “a campaign to encourage divestment from countries investing in Sudan.” Addressing Sudanese opposition groups in Nairobi, Kenya, last October, Albright said she was concerned about oil companies financing the Khartoum regime: “Part of the problem is that there seem to be more countries that believe that if a central government that is dictatorial has access to more money, that somehow that money will filter to the benefit of the people. That doesn’t happen.”

Goldman Sachs and CNPC have been scrambling to restructure the company they will introduce to Wall Street to isolate the Sudanese investment from the IPO. But the critics aren’t satisfied. In October, Rabbi David Saperstein, chairman of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, a federal advisory body, signed a letter to Clinton asking him to interdict the CNPC’s initial public offering.

In December, the 200 religious and human-rights leaders, joined by former Treasury secretary William Simon, Freedom House Chairman Bette Bao Lord and former Reagan national-security adviser William P. Clark, called on Clinton “to fully and vigorously enforce your own executive order of 1997 toward the China National Petroleum Corporation and other companies now providing massive oil revenues for the Khartoum regime.” They said the order “should be construed or amended to bar CNPC from access to U.S. capital markets so long as it continues to be a 40 percent partner in the Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Company project, and so long as that venture provides the regime with millions of dollars in annual oil revenue.”

Goldman Sachs’ attempt to circumvent the executive order and public censure by its “restructuring scheme,” they argue, is only window dressing: “The fungibility of money and the scale of CNPC’s activities in Sudan thoroughly undermine the credibility of this contrivance.”Not since the Russian gas monopoly Gazprom tried to issue its $3 billion bond offering in 1997 have so many U.S. lawmakers and national-security figures become so mobilized on a finance issue.

Sen. Sam Brownback, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations subcommittee on Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs, argued that Gazprom should not be allowed to raise funds in U.S. markets. “The bond offering would essentially result in U.S. investors funding activities which pose serious threats to U.S. national-security interests. And I can’t put it any blunter than that.” Issuing such bonds, he noted, also would create a U.S. political constituency for the Russian gas monopoly through the “new investors who will have a vested financial interest” in protecting the company.

The issue isn’t simply Sudan; it’s Communist China’s massive military modernization and buildup, its growing strategic nuclear-missile arsenal and its public adoption of what it calls “asymmetrical warfare” against the United States by penetrating the United States where it is most vulnerable: its computerized infrastructure and its economy. Policymakers and investors simply aren’t equipped to deal with the issue.

“Let’s not kid ourselves. We understand that there are those commercial interests who put on the back shelf the national interest and security of this country,” then-Senate Banking Committee chairman Alfonse D’Amato, a New York Republican, said in a 1997 hearing on how U.S. entities inadvertently are financing terrorist regimes. He used that rationale to discourage the proposed billion-dollar bond offering by the Russian gas monopoly.

Sen. Mitch McConnell, the powerful Senate Appropriations Committee chairman from Kentucky, agreed: “We know Iran is aggressively pursuing a nuclear-weapons program. U.S. agencies and institutions should not underwrite companies willing to generate profits for Teheran to buy or build that bomb.” He pledged to take “whatever steps are necessary” to oppose financing of Iranian oil fields through Gazprom.

The Republicans weren’t alone. Sen. Christopher Dodd, a Connecticut Democrat and a major political fund-raiser for his party, echoed his GOP counterparts’ concerns. That was 1997, and though the Gazprom offer was withdrawn, the transparency and disclosure efforts went nowhere legislatively. By its inaction, however, Congress paved the way for CNPC to issue its IPO.

Granting more power to the SEC gives many investors and conservative economists the creeps. Yet some state officials in Iowa and Tennessee say it’s up to the federal government, not the states or Wall Street, to warn them of national-security problems. That’s the constitutional argument Bachus and Kucinich are trying to address while keeping government out of the capital markets.

“To be sure, market analysts do not lack the expertise to perform the necessary economic and financial evaluations,” the William J. Casey Institute of the Center for Security Policy argues in a recent paper. “The problem is that they have, until now, seemingly failed to grasp the fact that governments and companies of concern to the United States from a defense and foreign-policy perspective are increasingly cloaking themselves as benign commercial/civilian enterprises, only too delighted to find that they can get away with exchanging paper promises to repay (in the case of bonds) or to provide return on investments (in the case of equity offerings) for hundreds of millions, or even billions, of dollars.”

And here is the constitutional argument: As this is a defense and national-security issue involving a foreign power, it is appropriate for the federal government to take the initiative to ensure sufficient transparency and disclosure.

“We have no interest in creating capital controls or implementing other broad measures that could damage the competitiveness and attractiveness of the U.S. capital markets,” according to Bachus, who says he and Kucinich seek to preserve the free flow of foreign capital into and out of the United States. “Rather, we are concentrating on strengthening disclosure and transparency requirements so that fund managers, Wall Street players and average American investors can make more-informed investment decisions.”

Their bill was aimed not at foreign private companies but foreign government-affiliated entities. They commissioned the General Accounting Office to examine all Chinese and Russian enterprises in U.S. markets and identify those with ties to military or espionage structures. The GAO study has not yet been initiated.

“We understand full well that the free flow of capital is a pillar of our leadership and competitiveness in the world,” says the Casey Institute’s Roger W. Robinson, a former Reagan National Security Council senior director of international economic affairs who is widely credited as being behind the global transparency and disclosure initiative.

“Undue government intervention would likely cast a pall over the markets and impede that flow. We’re not remotely looking to replicate COCOM [a U.S.-led international body to restrict militarily relevant technology sales to the Soviet bloc during the Cold War] in the financial arena or have the U.S. government determine what investors can or cannot buy,” Robinson tells Insight. “But we think American investors have a right to know the true identity, affiliations and activities of those foreign entities whose stocks and bonds they are purchasing.”

Former Rep. Gerald Solomon of New York, the House Rules Committee chairman who advocated creation of such an office three years ago before leaving Congress, says it’s important for the United States to monitor attempts by potentially hostile entities, particularly governments, to “engineer fluctuations” in U.S. markets – basically exploiting the market mechanisms to upset the U.S. financial system or influence U.S. politics.

“The proposals – I have seen some even in legislative form – to set up essentially a national-security office within the Securities and Exchange Commission have merit,” Cox of California told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in October. Cox has a reputation for being pro-defense and opposed to government regulations on business.

Cox’s concern is one of fairness as well as SEC national-security policy: “Insofar as we urge the openness of trade and investment throughout the world, we welcome it here in our own country and we don’t want to set up barriers to investment. But we also need to take a look at the degree to which disclosure, which is what the SEC is supposed to be all about, by foreign borrowers and foreign users of our capital markets does not measure up to disclosure by our own domestic companies.” In other words, simply require foreign issuers of stocks and bonds on U.S. capital markets to meet the same standards of transparency as U.S. companies. Cox saw the perils of nondisclosure up close in his home in Orange County.

“I come from a county that had the largest municipal bankruptcy in American history,” Cox says. “And one big reason behind that bankruptcy is that the level and quality of disclosure in an information statement for municipal borrowers is nothing compared to the quality of disclosure for a corporate borrower. Then, when you go to foreign governments, you find that the disclosure is far less adequate. When you go to governments that are as opaque, nontransparent, as the Communist government of the People’s Republic of China, where so much of enterprise is state-run, where accounting is as much creativity as hard figures, I think people are essentially lending money to the state of China, the Communist government of China, on the brand name and on the expectation that they will somehow pay it back, but not because of any substantive disclosure.”

SUBMARINES FOR PEACE?

If COSCO, the China Ocean Shipping Co., is a purely commercial freight enterprise as its defenders say, why is it adding new submarines to its fleet?

On Dec. 8, 1999, COSCO announced it had signed a contract with Guangzhou Ship Engineering to build two 18,000-ton “special-purpose” submarines. According to a COSCO news release, “The proposed building of these two submersible vessels is based on COSCO Guangzhou’s operation principle which focuses on special-purpose vessels.” COSCO adds, “The order of these two ships is also required by the formation of COSCO Guangzhou’s special-purpose fleet.”

The submarines, with European design features, contain what COSCO calls an “advanced electronic propelling system” – a system, in fact, based upon stolen U.S. technology that U.S. Navy officials tell Insight will make the vessels extremely difficult to detect.